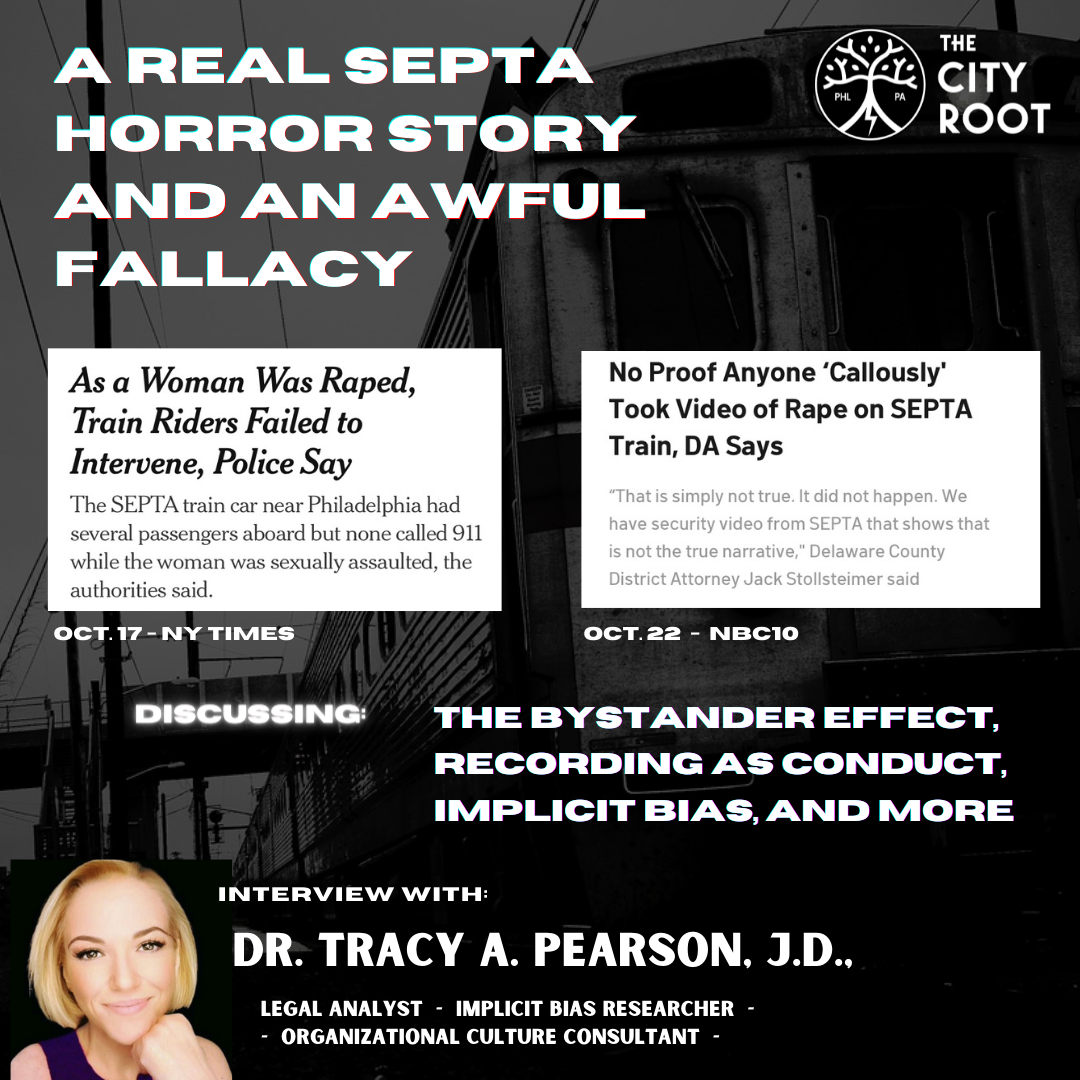

A Real SEPTA Horror Story and an Awful Media Fallacy

from our instagram: @thecityroot

Editor’s Note: This was originally slated to publish while the SEPTA rape/recording story was still unfolding in late 2021. However, as you’ll see, this article is about much more than a singular incident. It’s a larger conversation on the Bystander Effect, implicit bias, vigilantism, action and involvement in scary and complex legal situations, and more.

The conversation and interview with Dr. Pearson was initially sparked by the false report that SEPTA riders recorded the incident rather than intervened. It took place after police told reporters that people watched and recorded the event rather than stepping in, and after that came to light as a false report.

THE STORY

On October 13th, a woman was raped on SEPTA’s Market-Frankford line as it pulled into Upper Darby’s 69th Street station. Surveillance footage shows the woman boarding the train at 9:15 p.m., shortly before her assailant, 35-year-old Fiston Ngoy, does. He sits next to her, speaks to her, and touches her—all as she pushes him off repeatedly—until 9:52 when he begins raping her for six minutes. An absolutely horrific public event that surely degraded late-night SEPTA rides to “last resort” status for thousands, as if it wasn’t already.

After the crime was reported to 911—by an off-duty SEPTA employee shortly before 10 p.m.—a Transit Police officer boarded the train, discovered the assault in progress, and took Ngoy into custody, charging him with rape and involuntary deviate sexual intercourse.

Okay, so, first thought when I heard this story: How the hell did this interaction occur upwards of 45 minutes with, from the sounds of it, absolutely zero bystander intervention? Even for a Wednesday night, 9:52 is still fairly early, so was there no one else around? Did no one notice? How can such a heinous act happen—both the incessant harassment and subsequent assault—without being stopped?

Turns out, the answer to that question is extremely convoluted. So convoluted, in fact, that I’m writing about it a month after it occurred (and editor is publishing 6 months later) because the story keeps changing… but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Initially, what made this story especially jaw-dropping is what was first reported:

“ 'Angry and disgusted': Train riders held up phones, didn't call 911 as woman was raped on Philadelphia train, police say” (USA TODAY)

“As a Woman Was Raped, Train Riders Failed to Intervene, Police Say” (The New York Times)

“A woman on a SEPTA train was sexually assaulted while other riders failed to intervene, authorities say” (CNN)

“Riders held up phones as woman was raped on SEPTA train in Philadelphia, police say” (NBC News)

Yes, you read that right: it was reported by SEPTA officials and police that while this woman was being raped for six minutes, fellow riders not only did nothing to help her, but instead filmed the dreadful event. The narrative quickly spread and was picked up nationally.

We would later find out that was not the case, and we’ll get to the fuckery behind that situation later…

“There is a narrative out there that people sat there on the El train and watched this transpire and took videos of it for their own gratification,” Delaware County District Attorney, Jack Stollsteimer said using the nickname for the Market-Frankford line. “That is simply not true. It did not happen. We have security video from SEPTA that shows that is not the true narrative.”

But Why Film in Any Regard?

First, let’s discuss what would prompt a civilian to film a heinous act of any kind, rather than intervene…

To go viral? (for God’s sake I hope not, but this is an all too common occurrence)

For some form of personal, sadistic pleasure? (please, god, no)

To create evidence of the crime? (hopefully)

I interviewed Dr. Tracy A. Pearson, J.D., Legal Analyst, Implicit Bias Researcher, and Organizational Culture Consultant, to discuss the bystander effect further. She is based out of Los Angeles and her research involves implicit bias in investigations. In fact, she conducted the first study of implicit bias in workplace investigations.

This interview took place after the rape and recording was reported nationwide, but before the recording aspect turned out to be false.

“There is a level of callousness that hangs like a pall over this event to the casual thinker,” explains Dr. Tracy A. Pearson.

“Watching someone be raped is particularly depraved because the act of rape is a violation and degradation of the human body.”

“But, to answer your question [about why people would want to record the attack], I want to generalize the behavior,” she continues. “Sex can heighten emotions and impact analysis. Every day, numerous incidents of assault and other unlawful conduct occur where witnesses record the event rather than physically assert themselves to disrupt the event. Those that choose to document the event are hailed as courageous. A good example of that would be the witness who recorded the murder of George Floyd, Darnella Frazier. That video allowed prosecutors to understand and prove what happened in detail in the last moments of Mr. Floyd's life.”

Well, damn… I never thought of it that way. Further, had Darnella stepped in to intervene, it’s almost certain she would have been struck, injured, and/or arrested herself. Not that any of that is justified.

And she’s right, of course, because recording sends a message. It tells the person engaging in the unlawful act that they’re being watched, documented, and, as a result, will probably be arrested and be punished for their actions.

It’s also much, much safer.

“Context is important to understanding these situations, which are fact-specific, and it is unfair to judge them without that information.”

“In the situation of someone shouting racial epithets at an individual the risk is lower, in theory, depending on the community and attendant circumstances (risk of weapons, for example), and a person may feel safer to act in aid of another,” says Dr. Pearson.

A DREADFUL EXAMPLE

Take 9/11, for instance, and the people aboard Flight 93 who so courageously took down the hijackers, forcing a crash landing in an open field in the middle of rural Pennsylvania instead of the intended target of the nation’s capital. Or the teacher-heroes who take down gunmen in school shootings. Or the million other examples of barbarous acts of mass murder, injustice, and genocide that have occurred around the world over the centuries. Because while we can sit here today and say we would have always been on the right side of history, that’s much easier said than done, decades later, without our lives and the lives of our families on the line.

Author Note: Though this rape didn’t result in a homicide, I’d be remiss to not mention the fact that it occurred in a year that was the deadliest in Philadelphia homocide history.

Also, since only one-third of sexual assaults are even reported to the police, I wanted to acknowledge that while this case is horrific, it is by no means isolated.

Yet… while filming is necessary, it’s also a bit of a cop-out, no?

We’re not all Harriet Tubmans, Mothers Theresas and badass Marines.

And because of that, who are you—and who am I?—to say what you would have done during the SEPTA rape had you been there? Whether you’re male or female, big or small, young or old, military veteran or not, you really don’t know how you would handle any particular situation until you’re in it. You just don’t.

BUT SOMEONE’S GOT TO Step Up

We can’t all film violent acts.

We can’t all be witnesses.

Some of us—one of us—has to intervene.

From the NBC10 article:

Stollsteimer emphasized that it is not unlawful to avoid intervening when witnessing a crime, and he asked anyone who may have seen the rape to come forward

Who’s going to step up?

“Why the choice to act was to record the crime and not intervene physically can be explained by understanding implicit bias,” explains Dr. Pearson. “There are many implicit biases, but the oldest implicit bias we have is survival. The human body is designed to do everything possible to survive. The brain searches patterns learned over a lifetime, simultaneously predicting the probability of outcomes, and a person makes a decision. In a closed environment, like a train, where you can’t escape easily, where there is a heinous act so unconscionable as rape, where weapons might be present, the decision to record the event and not aggressively confront the situation is inherently tied to the implicit bias of survival.”

For a more granular, everyday understanding of implicit bias, it’s locking your doors around certain people or in certain neighborhoods. It’s expecting your doctor or the “person-in-charge” to be a man. It’s asking your female coworker if she has a boyfriend without knowing anything about her sexual orientation.

However, implicit bias certainly holds less weight to a bystander in a rape case.

“I think the Bystander Effect as I have explained it—a moral judgment that one put themselves at risk to save another—is unreasonable in certain situations,” Dr. Pearson continues. “For example, in a situation where there is a violent act, like the murder of Mr. Floyd, some individuals attempted to intervene, but the power and privilege of law enforcement knocked down any effort to rescue, such that the conduct that was heralded was the recording of the event by a bystander. Yet, by contrast, the people on the train are being criticized for not physically intervening.”

The Story Evolves

Speaking of law enforcement, remember when I mentioned how convoluted this appalling tragedy has become over the past month? Well…

Police Lies About SEPTA Riders Filming a Rape Show Yet Again Why We Can’t Trust Them (Philadelphia Magazine)

Philadelphia police account of bystanders filming rape on train wasn’t true (Yahoo!)

Police said bystanders saw a rape on the train but failed to stop it. The DA now says that didn’t happen. (The Washington Post)

TLDR: As if the city of Philadelphia needed yet another disparaging reason to make the news, police’s account of the SEPTA rape only added national and international finger-wagging to the gamut, by telling any and every news outlet that would listen that, essentially, its own citizens have no goddamn souls for filming the attack instead of calling it in, let alone intervening.

This turned out to be false, similar to the over-sensationalized rape and murder of Kitty Genovese in the 60s, where 38 people were reported to have, too, ignored her and her cries for help.

Despite all the press immediately, and somewhat understandably blaming the police, NBC10 noted that DA Stollsteimer placed the misinformation blame on SEPTA officials.

Still, I don’t think we’ll ever get a sufficient direct answer on where the rumor got it’s first legs.

Do I think law enforcement intentionally lied?

I don’t.

Maybe I’m naive. I probably am. But in this case, specifically, I think they really, truly thought that’s what happened, so they wanted to do and say whatever they could to make their disgust at both the act and the actions (or inactions) of those present abundantly clear.

Do I think the police lie?

I sure do.

Just look at the original press releases of the George Floyd murder.

When they or their colleagues make mistakes, they lie. When they don’t know how to handle a situation or know they should have handled it better, they lie. When they feel it’s necessary, they lie or stretch the truth to the point it’s more digestible for the public to accept or sway in a particular direction, away from the fire at hand.

Most of the time it’s probably just to cover their own asses.

We all do it. Or, at least we all have. As humans, in all industries, in all walks of life.

But we’re not all cops or SEPTA officials.

So, our lies—and our implicit biases—don’t affect public safety.

Now, this is not an anti-cop article. I’m not anti-cop. And it’s not because I’m married to one, or my Dad is one, or some sort of bull shit like that. (In fact, I only know, like, one cop.) There is no blue lives matter slogan on my Honda Civic because it’s a ridiculous mantra, and everyone fucking knows it because blue lives have always mattered.

I like cops because they’re important to maintaining law and order, but they undoubtedly CAN overstep their bounds, be trigger-happy, benefit from education on how to deal with marginalized communities, and be racist, sexist, bigoted narcissists.

They’re also under-appreciated, underpaid, and over-utilized.

You couldn’t pay me a million dollars in the world to be one, so I’m not one.

Anyway, I say all of that to say this:

Because we—you, me, everyone, everywhere—can all stand to be a lot nicer and kinder to one another, here are five ways to be a better, more active bystander, an upstander, if you will (courtesy of the lovely Dr. Pearson):

Put on your oxygen mask before helping someone else with theirs. The rationale is simple; you cannot help someone else if you are at risk. The same holds true with being a bystander. You have to prioritize your own safety. No one should be putting themselves in harm’s way to rescue another as a matter of rule.

Do not escalate the situation, as escalation can result in more harm to the person you are trying to help and to yourself.

Make your presence known in a safe manner.

Attempt to distract, but only if intervention is appropriate and safe.

Understand that questions or observations can be more effective over accusations or demands, as long as you're not escalating the situation. For example, if you notice someone who is in danger because of intoxication you might say, “Hey, she looks drunk.” Then, you might distract the offender with a question to the person at risk, “Would you like to come with me?” Take your cues from the person perceived to be at risk—in some situations, especially with domestic violence, overt attempts to rescue, especially unsuccessful ones, can be deadly for the person being victimized. If direct intervention is not viable, most jurisdictions permit recording in a public space where there is no expectation of privacy (states differ on whether it is lawful to record another person without their consent), especially if documenting the event may provide help to authorities.

What I’m getting at is this…

We can be vigilant without being vigilantes.

We can intervene without being seen.

We can—and must be—decent people.

So for those who do intervene on behalf of a victim—cops and civilians alike—thank you.

You’re important and we need more of you.